For two weeks, doctors stood beside his hospital bed and called his name.

There was no response.

On January 24, 1961, Mel Blanc was driving along Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles when another car slammed into him head-on at a notoriously dangerous bend known as Dead Man’s Curve. The crash nearly killed him. His legs were shattered. His pelvis was broken. He suffered multiple skull fractures so severe that rescuers needed half an hour just to cut him free from the wreckage.

When he arrived at UCLA Medical Center, he was unconscious.

Mel Blanc slipped into a deep coma.

For fourteen days, his family and medical team tried everything. His wife spoke softly to him. His son leaned close and said his name again and again. Nurses and doctors repeated “Mel,” hoping for the smallest flicker of awareness.

Nothing came back.

It was an unbearable silence, especially considering who Mel Blanc was.

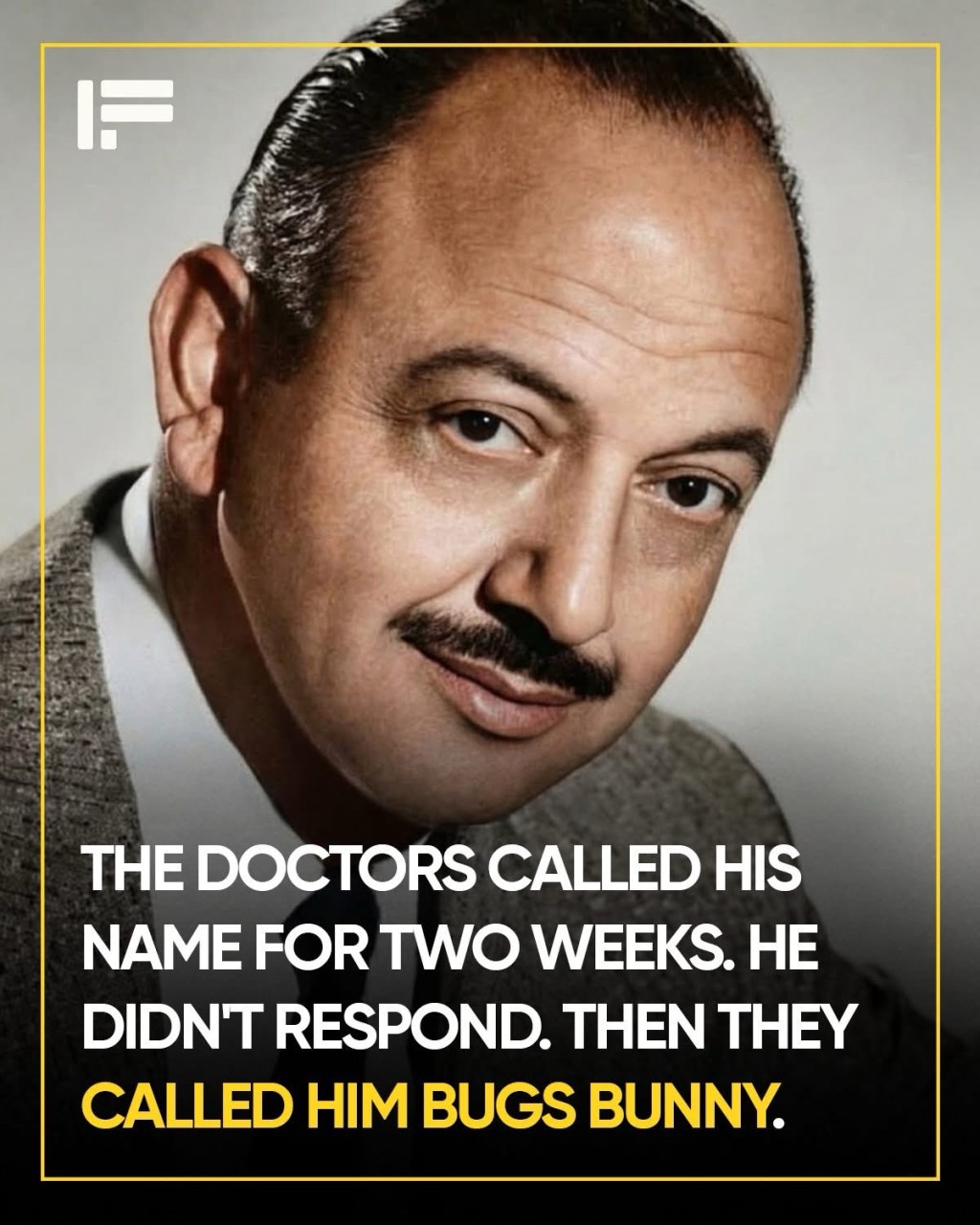

By 1961, he was the most recognizable voice in American entertainment, even if few people recognized his face. He was the man behind Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Porky Pig, Tweety, Sylvester, Yosemite Sam, Foghorn Leghorn, Speedy Gonzales, and dozens more. He was known as “The Man of a Thousand Voices,” a title that barely captured how deeply he embodied each character.

Mel did not merely perform voices. He became them. His expressions, posture, and breathing all shifted depending on who was speaking. Those characters were not separate from him. They were part of him.

Which is why what happened next stunned everyone in the room.

One of his neurologists, Dr. Louis Conway, decided to try something unconventional. Instead of calling him Mel, he leaned over the bed and asked a simple question.

“How are you feeling today, Bugs Bunny?”

There was a long pause.

Then, faint but unmistakable, a voice answered.

“Eh… just fine, Doc. How are you?”

The room froze.

The doctor tried again, this time calling out another character.

“Tweety, are you there?”

“I tawt I taw a puddy tat.”

Against all expectations, the voices emerged before the man did. The characters Mel Blanc had created were more accessible to his injured brain than his own identity. When addressed as Bugs Bunny or Tweety, he responded faster, clearer, and with more awareness.

Those voices became the bridge that guided him back.

Recovery was long and painful, but Mel Blanc did something extraordinary. While still in a full-body cast, unable to sit up, recording equipment was brought directly into his hospital room. Scripts were held above his face. His son turned pages for him. Fellow actors gathered around his bed.

From that position, Mel continued voicing Barney Rubble on The Flintstones and his Looney Tunes characters, refusing to let injury silence him.

He returned to work fully and continued performing for nearly three more decades, with his final role appearing in Who Framed Roger Rabbit in 1988.

When Mel Blanc passed away in 1989 at the age of 81, his gravestone read:

“That’s All Folks.”

But his real legacy had already been written years earlier in a hospital room, when the doctors called his name and he could not answer, yet called him Bugs Bunny and brought him back.

It was not magic.

It was identity.

The characters were not just voices. They were home.

Leave a comment